Isabel Díaz Ayuso has risen out of nowhere to political stardom. In Madrid, the regional president is on the verge of her next triumph, a success story that could pull Spanish conservatives to the right.

At some point, long after the mass has been read, the priest has had enough. He hisses into the microphone, loud and sustained: “Sh-sh! “Sh-sh! Sh-sh!” A crowd has formed in front of the altar in his church in the center of Madrid. Retirees, businesspeople, nuns and children are all elbowing each other out of the way, fighting for a selfie, as they try to get closer to the woman they adore.

Isabel Díaz Ayuso, 44, president of the Madrid region, is standing in a magenta dress in the middle of the cluster of people, wrapped in a mist of incense. She is squeezing forearms and hands. Her fans have been waiting for their chance for more than an hour, and now they wrap their arms around her.

The increasingly desperate priest pleads: Please take your photos outside on the street. But no one is listening.

Ayuso isn’t particularly pious, but that doesn’t matter to the devout on this particular day. The capital city is in the middle of an election campaign, with less than a week to go until regional and local elections. “Madam president, my lovely, you have to win,” shouts one retired woman. “She’s done so much for Madrid,” says a chubby-cheeked 24-year-old with dark curls. Ayuso squeezes him, too, as tears well in his eyes.

Few Spaniards had even heard of Ayuso a couple of years ago. Now, the former journalist governs Madrid, one of the country’s most important and powerful regions. Ayuso has become a star of the conservatives. Within her party, few dare to question Ayuso’s power, and there has even been speculation that she might ultimately seek the Spanish presidency.

In Spain, Ayuso is either loved or loathed. Children wear T-shirts printed with her image, and some bars have photos portraying her as the Virgin Mary. But her critics paint her as a danger. She reminds them of Donald Trump and they wonder where it will all lead.

There’s never a dull moment with Ayuso. Sometimes she downplays climate change, sometimes she tells an opposition leader to do her crying at home. During the pandemic, she lambasted Podemos, the left-wing coalition partner in Pedro Sánchez’s government, as being “worse than the virus.” She’s known for lines like: “When they call you a fascist, you know you’re on the right side of history.”

After a glass of wine, one leftist politician admits: “It’s like rubber-necking a car accident. I just can’t look away.”

Díaz Ayuso: When she appears on television, the ratings rise.

Foto: Gustavo Valiente / Europa Press / Getty Images

Ayuso is hoping to expand her power in Madrid in the nationwide regional elections on May 28, and according to polls, around 47 percent of voters intend to cast ballots for her party. She is aiming for an absolute majority, and right now, her approval ratings are reminiscent of times when only two major parties vied for power in Spain: the Socialists and the People’s Party.

Just who is this woman? How can her success be explained? And what does it mean for Spain?

On a hot, early summer day, Ayuso is sitting in sneakers and jeans in the announcer’s booth of a sports stadium in an affluent Madrid suburb, and she’s rather annoyed. Ayuso has just opened a children’s sports competition, dancing around in the stands as the kids warmed up below. But as she spoke, she complains, she could only hear herself, and the echo made her feel insecure. It’s something that rarely happens to her on a political stage.

Ayuso grew up as the younger of two siblings in Madrid’s posh Chamberí neighborhood. She didn’t have a good relationship with her father, a businessman. “He was really hard on me,” she once said. She studied journalism in college and moved out of her family home at the age of 22.

The past four years as regional president have completely changed her life, she says. The pandemic, a fierce winter storm, the war in Ukraine – it seems all she did was work the whole time.

Ayuso talks about the time she worked from a hotel because she had come down with the coronavirus. The father of a good friend died during that time, Ayuso had known him since childhood. She says they were the most difficult months of her life.

A member of the conservative People’s Party, Ayuso has been sharply criticized for her loose coronavirus containment policies. She allowed restaurants and bars to largely stay open, and there were times when masses of young French people flew to Madrid to party. The city paid an enormous price for her policies: Madrid recorded one of the highest death rates in Spain during the pandemic. Reporting by the Spanish media also found that, during the first, particularly horrible wave of the pandemic, Ayuso’s government prevented ill senior citizens from being taken from nursing homes to crowded hospitals. Thousands of people died because they didn’t receive medical treatment.

In the meantime, though, there are many who are grateful to her for not forcing them to stay in their homes at the time. Ayuso also remains convinced to this day that she did the right thing. “I would do it all over again the same way,” she says.

The rather quiet Ayuso, sitting in the stadium announcer’s booth during her interview with DER SPIEGEL, has little to do with the woman who speaks to her supporters in a park shortly afterward. As Ayuso takes the stage and begins her speech, her features harden. She shouts that Spanish Prime Minister Sánchez wants to turn Spain into an ultra-leftist country. That Sánchez is weakening the monarchy and the capital. She tells them that he and his people “despise Madrid because Madrid doesn’t elect them.” And that Sánchez lies every day. That he treats people like cattle. The crowd applauds.

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez is a popular target of Ayuso.

Foto: Christina Quicler / AFP

It’s Ayuso the demagogue who is speaking now. She sinks her teeth into Sánchez, the rather harmless Social Democrat leading the country, and doesn’t mention to the political competition in the Madrid region even once. It seems that she outgrew them long ago.

Listening to the stage version of Ayuso, it’s easy to see why she’s even more popular among supporters of the radical right-wing Vox party than among her own PP. Vox is weaker in Madrid than elsewhere, and Ayuso deserves some credit for that. But she has no qualms about working together with the right-wing radicals and didn’t seek to distance herself from them until shortly before the regional elections.

Most mornings, Ayuso already knows the message she wants to make it into the media that day. The man many believe is responsible for that receives his guests at the presidential palace on Puerta de Sol. Miguel Ángel Rodríguez, Ayuso’s communication director, has two ashtrays in his office. He stores a box of red wine under the table, and his shirt sleeves are embroidered with the initials by which he has been known in Madrid for decades: MAR.

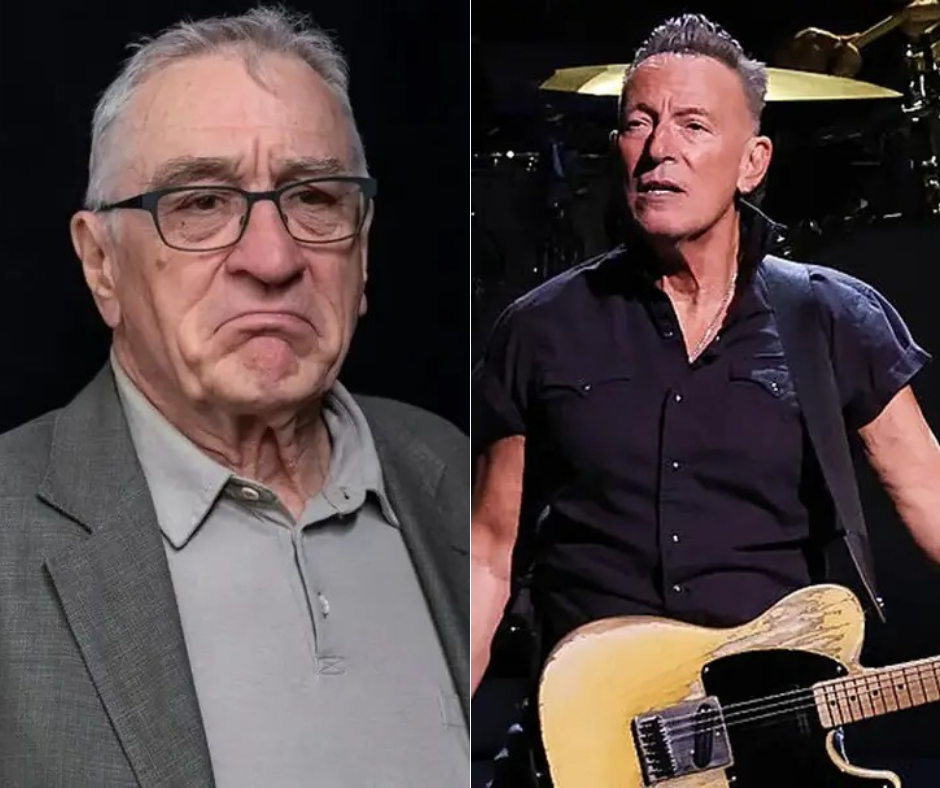

Many believe the Ayuso’s communication director, Miguel Ángel Rodríguez, has played a major role in her success.

Foto: Carlos Lujan / Europa Press / Getty Images

Rodríguez, 59, a bearded man with a furrowed face, once advised conservative politician José María Aznar and helped pave the way for him to become prime minister. People in Madrid suspect he has the same plans for Ayuso.

The Ayuso way is also the MAR way – when she makes appearances on TV, the ratings go up, he says. And the TV stations are fully aware of that, he says. That’s why, for years now, everything has revolved around Ayuso – all the stations need her pugnacity for their ratings. She sets the agenda, and her competitors riff on her and her positions – not the other way around. Ayuso’s approach works because Spanish society is already polarized, a development she is further reinforcing.

“Madrid is Spain” is one of Ayuso’s favorite lines. It’s also the home of all the people who come to the capital city to build a new life through hard work. If you listen to Ayuso for long enough, you get the impression that Madrid is the center of the world. “Chulería madrileña” is how they describe that in Spain: Madrilenian pomposity.

If Ayuso were locked in the container of the reality TV show “Big Brother,” she would stand a good chance of winning. Recently, she sat in the audience at the Los40 Music Awards when the half-naked reggaeton singer Anitta danced over to her unexpectedly. Ayuso laughed, raised her hands and enjoyed the spectacle. It’s scenes like this on which her cult status is based.

Ayuso is now largely immune to criticism, says Antonio Maestre. The left-wing journalist has memories of her from the time they competed against each other on political talk shows.

Donald Trump once said he could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue and still not lose any voters. Maestre says that’s how far Ayuso has come. He says she is ruining Madrid’s public health system and that she’s involved in shady deals. During the pandemic, her government awarded a contract to her brother, who procured masks from China. “None of it has hurt her.”

People on Ayuso’s team indignantly reject that comparison, but political scientist Ignacio Sánchez-Cuenca also describes Ayuso’s political style as a sort of “Trumpism.” The question many in Spain are currently asking is this: Does such a person also stand a chance outside of Madrid? Will Ayuso become prime minister one day?

Spaniards will go to the polls at the end of the year to elect a new parliament. The leading candidate with Ayuso’s conservative PP, Alberto Núñez Feijóo, is in many ways the antithesis of the colorful Ayuso. He’s a serious, slightly dull politician, a candidate at the political center who isn’t built for culture wars. But since Feijóos’ popularity has started waning in the public opinion polls, his rhetoric has also taken a shriller turn.

Ayuso has already taken down one party leader – Feijóos’ predecessor, and people close to the lead candidate are clearly nervous. One recently remarked to journalists that Ayuso’s policy blueprint is reminiscent of Liz Truss, the short-lived British prime minister who failed miserably with her tax-cutting plans and ended up being mocked even by Prince Charles.

Ayuso, of course, denies wanting to take over from the party’s lead candidate. She says her place is in Madrid. But if you let her talk long enough, she also says things like: “It’s true that many citizens would like to see me as the head of government.” But she says her party already has a candidate: Feijóo.

There’s much to suggest that Feijóo may indeed be allowed to try his luck in the election at the end of the year – and that he will have to go if he doesn’t win. That’s when Ayuso’s hour could strike. “She would be the logical successor,” says political scientist Pablo Simón. “Under her, the People’s Party would move further to the right.”

The big Ayuso show, which she has so far been performing mainly in Madrid, would then be making stops all across Spain.